In my latest American travel memoir, Turn Left at the Trojan Horse, I passed through a town called

Laporte, located in the Endless Mountains of Pennsylvania. There I met a

remarkable woman who called herself Mollie Sheldon Elliot. It turns out that

Mollie, Sheldon, and Elliot are three of more than a dozen disparate

personalities within her, the products of dissociative identity disorder

stemming from childhood molestation. Each is aware of the others, a group that

includes a baby, a teenager, a fellow who speaks with an Irish brogue, even an

elderly Native American man. When talking about herself, she uses the pronoun

“we.”

“We started out with four of us who were together all the time,

and then we began to suspect—and that was part of the midlife crisis—that there

were other personalities hanging around,” she told me. “We sensed that there

were more, and we’ve had a series of alters—that’s the word psychologists

use—show up. We kind of view it as coming in from the cold.”

She is, in fact, a warm and intelligent woman—and an

author. A

few years back, she wrote an autobiography about her experiences. She called

the book Portrait of Q, which is what she calls the system that

constitutes herself. The Trekkie in me understood the reference immediately. Q

was a recurring character on “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” who possessed

both an individual and communal perspective as part of the Q Continuum, an

omnipotent collective of beings who seemed to guide the fortunes of mankind.

So in honor of Mollie Sheldon Elliot—really, in honor of Q, my

favorite pen name—we at the Why Not 100 offer an alphabet of literary

information that might someday be useful, if only to impress your friends:

A is for A.A. Milne,

who first published Winnie-the-Pooh

in 1926. Yep, the hyphens were there at first—until Disney adopted the books

into a series of features and dropped them. Did you know it was translated into

Latin (Winne Ille Pu) and in 1960 was

the first Latin language book ever to hit The

New York Times bestseller list? Did you know that Milne had a son name Christopher

Robin? Did you know that Christopher named his toy bear after “Winnie,” a

Canadian black bear at the London Zoo who had in turn been named by the hunter

who captured him after his adopted hometown of Winnipeg? Did you know that Pooh

had been the name of a swan? Now you do.

B is for Junie B.

Jones, the bestselling children’s book series by a couple of B’s—author

Barbara Park (who sadly died at age 66 in 2013) and illustrator Denise Brunkus.

The character’s middle initial stands for Beatrice, and Juniper Beatrice Jones

has been featured in more than two-dozen books since the original (June B. Jones and the Stupid Smelly Bus)

in 1992. Among the best titles are Junie

B. Jones and… Her Big Fat Mouth

(1993), the Yucky Blucky Fruitcake

(1995), and the Mushy Gushy Valentime

(1999). In 2001, she finally graduated from kindergarten to first grade.

C is for vitamin C,

which has been the subject (believe it or not) of numerous books. Among the

titles are these: Vitamin C and the

Common Cold; Cancer and Vitamin C; Vitamin C: The Master Nutrient; Vitamin C:

The Real Story; Ascorbate: The Science of Vitamin C; The Vitamin C Controversy;

Curing the Incurable: Vitamin C, Infectious Diseases, and Toxins; and Vitamin C The Future is Now. Depending

on which national agency you respect most, an intake of 40-100 milligrams of

Vitamin C daily is recommended.

D is for D-Day. Rave

all you want about Steven Spielberg’s WWII epic film Saving Private Ryan, but it’s another Ryan—Cornelius Ryan—who wrote

the definitive book about D-Day. Although there have been numerous books

written about the massive Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, the best

might be Ryan’s The Longest Day. It

was written in the late 1950s when the participants’ memories were still vivid.

Ryan, who spent three years interviewing D-Day survivors on both sides of the

Atlantic, combined personal stories with a sweeping narrative, and historians

generally have relied on his research to bolster their own subsequent versions

of the invasion. Ryan later wrote A

Bridge Too Far about the airborne invasion of Holland.

E is for the e-book.

So who should get credit for inventing it? Should it be Bob Brown, who wrote an

entire book in the 1930s about a theoretical invention of a reading version of

the “talkie?” Should it be Roberto Busa, who prepared an annotated electronic

index to the works of Thomas Aquinas in the late 1940s? Should it be Andries

van Dam, who headed the Hypertext Editing System at Brown University in the

1960s and likely coined the term “electronic book?” Maybe. But we prefer to

give the credit to Angela Ruiz, a teacher from Galicia, Spain, who patented the

first electronic book in 1949. Why? Because she thought it was be easier for

her students to carry fewer books to school.

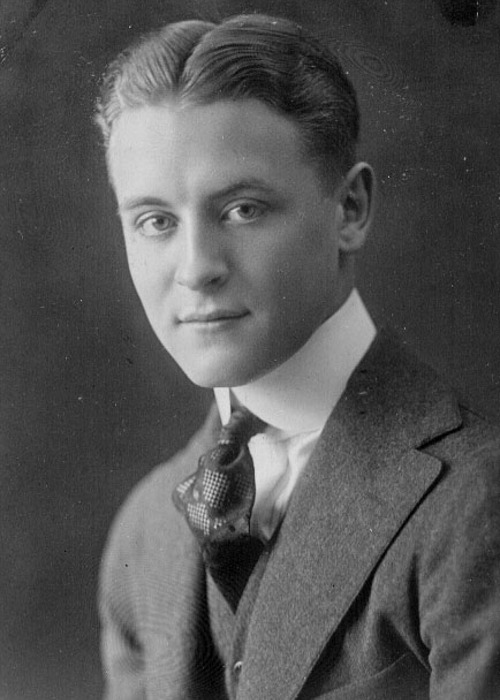

F is for F. Scott

Fitzgerald. Here are four fascinating facts about Fitzgerald: 1. Before he

was a novelist, he was an ad man. In My

Lost City, he later wrote, “I was a

failure—mediocre at advertising work and unable to get started as a writer.” 2.

Other titles that Fitzgerald considered before settling on The Great Gatsby included Incident

at West Egg, The High-Bouncing Lover, Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires, and

Gold-Hatted Gatsby. 3. The original screenplay for the film adaptation of

that classic was written by Truman Capote. It was rejected. Francis Ford

Coppola then finished his own draft in three weeks. 4. Fitzgerald’s advance for

The Great Gatsby was $3,939. He made

$16,666 off the movie rights.

F is for F. Scott

Fitzgerald. Here are four fascinating facts about Fitzgerald: 1. Before he

was a novelist, he was an ad man. In My

Lost City, he later wrote, “I was a

failure—mediocre at advertising work and unable to get started as a writer.” 2.

Other titles that Fitzgerald considered before settling on The Great Gatsby included Incident

at West Egg, The High-Bouncing Lover, Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires, and

Gold-Hatted Gatsby. 3. The original screenplay for the film adaptation of

that classic was written by Truman Capote. It was rejected. Francis Ford

Coppola then finished his own draft in three weeks. 4. Fitzgerald’s advance for

The Great Gatsby was $3,939. He made

$16,666 off the movie rights.

G is for G. Gordon

Liddy, who spent nearly 52 months in prison after being revealed as the

chief operative for the White House Plumbers unit during the Nixon Administration

and man behind the burglaries of the Democratic National Committee headquarters

in the Watergate building in 1972. Eight years later, he published an

autobiography titled Will, which sold

more than (ugh) one million copies and was made into a TV movie. In the book,

Liddy claims that he once made plans to kill investigative journalist Jack

Anderson—only because he heard someone in the White House say, “We need to get

rid of this Anderson guy,” and he interpreted it literally.

H is for H.G. Wells.

On the one hand, Herbert George Wells was a prolific writer well beyond the

science fiction genre, dabbling in everything from history and politics to

contemporary novels and textbooks. Yes, he wrote The War of the Worlds, The

Time Machine, and The Invisible Man.

But he also wrote titles like The Outline

of History. On the other hand… he once married his cousin, a union that

lasted four years until he left her for one of his students, whom he married,

though he later fathered two children with two other women. So either way, he was more than just the father of

science fiction.

I is for I, Claudius, the 1934 novel by Robert Graves, which has one of the

quirkiest and most memorable openings in literature: I, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus This-that-and-the-other

(for I shall not trouble you yet with all my titles) was was once, and not so

long ago either, known to my friends and relatives and associates as “Claudius

the Idiot,” or “That Claudius,” or “Claudius the Stammerer,” or

“Clau-Clau-Claudius” or at best as “Poor Uncle Claudius,” am now about to write

this strange history of my life; starting with my earliest childhood and

continuing year by year until I reach the fateful point of change where, some

eight years ago, at the age of fifty-one, I suddenly found myself caught in

what I may call the “golden predicament” from which I have never since become

disentangled.

J is for J.R.R.

Tolkien—that’s John Ronald Reuel. At the age of 16, he met Edith Mary

Bratt, and they fell in love. But Tolkien’s guardian (a strict Catholic who had

raised him after Tolkien’s mother died) forbade him from even corresponding

with the Protestant girl until he was 21. He reluctantly complied until his 21st

birthday, on which he wrote to her, declaring his love. She thought he had

forgotten her and told him that she had agreed to marry another man. But they

met beneath a railway duct and renewed their love (Edith returned her

engagement ring). They were married for nearly six decades until Edith died in

1971. Tolkien’s classic The Silmarillion

tells the tale of Luthien, the most beautiful of all the Children of Illuvatar,

who forsook her immortality for her love of the mortal warrior Beren. When

Tolkien died 21 months after his beloved wife, he was buried in the same grave

as Edith. On the tombstone are the words Beren

and Luthien.

K is for Knifeball, the name of a book by Jory John and Avery

Monsen—“an alphabet of TERRIBLE advice.” Poems and adorable illustrations

suggesting awful decision-making.

A is for Apple. Eat one ever day.

And

then wash it down with your mom’s cabernet.

B

is for blender. Your daddy won’t mind

if

you drop in his Rolex and set it to grind.

C

is for cop with a big shiny gun.

Sneak

up and tickle him. That’ll be fun.

It only gets worse (better really) from there… F is for

setting Daddy’s wallet on fire (and then REALLY hearing F-words), O is for

opening things with your teeth, and R is for raccoon (but definitely not

rabies). Previously, the authors wrote the even more successful picture book All My Friends Are Dead.

L is for Louis

L’Amour. At the time of his death in 1988, more than 100 of his books were

still in print. A complete collection of his works can be found at the Louis

L’Amour Writer’s Shack, which is tucked into the end of a re-created prairie

town called Frontier Village in Jamestown, North Dakota. That village is

surrounded by a herd of bison and the National Buffalo Museum, as well as the

World’s Largest Buffalo—a sculpture 26 feet tall, 46 feet long, built in 1959

out of 60 tons of concrete.

M is for M. Night

Shyamalan, the Indian-American screenwriter and film director of

supernatural successes like The Sixth

Sense, Signs, and The Village. Shyamalan

(the M is for Manoj) grew up a Steven Spielberg fan, and by the time he was 17

he had used his Super-8 camera to produce 45 homemade movies. In 2004, the

Sci-Fi Channel produced a “documentary” special called “The Buried Secret of M.

Night Shyamalan,” in which it claimed that the writer-director had once been

dead for nearly a half-hour while drowned in a frozen pond following a

childhood accident before being rescued and that he had afterward communicated

with the supernatural. It was all a hoax. Shyamalan was in on it. Sci-Fi’s

parent company, NBC Universal, issued an apology. M is for misstep.

N is for Stephen

King’s “N”. N is for novella (it appeared in his 2008 collection Just After Sunset). N is for two

narratives—one about a psychiatrist treating a patient known only as “N” and

the other following the psychiatrist’s sister exploring why her brother

committed suicide. N is for neurotic (“N” suffers from OCD and paranoid

delusions). N is for numbers. The patient is convinced that people who see

seven stones in a nearby field instead of eight may allow a monster to break

through into their reality. In fact any odd numbers are bad, especially prime

ones. Finally, N is for a newspaper clipping revealing that (spoiler alert)

after “N” kills himself and his psychiatrist follows suit, so does the shrink’s

sister.

O is for O. Henry.

His real name: William Sydney Porter. Actually it was William Sidney Porter, but for some reason he

changed the spelling of his middle name when he was in his thirties. More

quirky facts: He once started a satirical weekly called The Rolling Stone. For years, he gathered ideas for his columns and

stories by loitering in hotel lobbies and observing people there. In 1896, he

was arrested for embezzlement from a

bank and fled to Honduras. He later spent three years in prison, publishing 14

stories under pseudonyms while under lock and key. One of the pseudonyms was

“O. Henry,” which first appeared over the story “Whistling Dick’s Christmas

Stocking.” He once mentioned that the “O” stood for “Olivier.” A heavy drinker,

he died in 1910 of cirrhosis of the liver. There are elementary schools named

for this alcoholic-embezzler-writer in North Carolina and Texas.

P is for P.G.

Wodehouse. During a career that lasted more than seven decades (until his

death in 1975 at the age of 93), English humorist Sir Pelham Grenville

Wodehouse produced a diverse body of work—poems, plays, novels, short stories

and song lyrics. His fans and supporters have included the likes of George

Orwell, John Le Carre and J.K. Rowling. But he had his critics, including A.A.

Milne (see above) of Winnie the Pooh

fame. Wodehouse responded by wiring a short story parody called Rodney Has a

Relapse, which included an absurd character named Timothy Bobbin. Another

critic, playwright Sean O’Casey, called Wodehouse “English Literature’s

performing flea.” When Wodehouse produced a collection of letters to a friend,

he gave it the title Performing Flea.

Q is for Q from

the James Bond films, who is obliquely referenced by never actually appears in

any of the Ian Fleming novels. Short for “Quartermaster,” it is actually a title,

not a name, as he (or she) serves as head of the fictional research and

development division of the British Secret Service. Among the best gadgets that

Q has provided for Bond over the years: a wrist-mounted dart gun in Moonraker, a hydroboat fitted with a jet

engine in The World is Not Enough, a

stun gun/car remote control/fingerprint reading cell phone in Tomorrow Never Dies, a Lotus Esprit that

could transform into a submarine in The

Spy Who Loved Me, and an Aston Martin outfitted with a cloaking device in Die Another Day.

R is for R. In The World is Not Enough, Bond fans were

introduced to an assistant to Q, played by the irrepressible John Cleese, who

initially portrayed him as somewhat awkward and clumsy. Bond asked the elder Q,

“If you’re Q, does that make him R?” And that’s how Cleese was credited in the

film. After R proved himself via cool gadgets and cool-enough professionalism,

Bond began referring to him as Q.

S is for “S,”

published in 2013. Here’s The New

Yorker’s Joshua Rothman’s take on it: “S,” the

new mystery novel by J. J. Abrams and Doug Dorst, may be the best-looking book

I’ve ever seen. From the outside, it looks like an old library book, called

“Ship of Theseus” and published, in 1949, by V. M. Straka (a fictitious

author). Open it up, though, and you see that the real story unfolds in

Straka’s margins, where two readers, Eric and Jen, have left notes for each

other. Between the pages, they’ve slipped postcards, photographs, newspaper

clippings, letters—even a hand-drawn map written on a napkin from a coffee

shop. To solve the book’s central mystery—who is V. M. Straka, really, and what

does he have to do with Eric’s sinister dissertation advisor?—you have to read

not just “Ship of Theseus,” but all of Jen and Eric’s handwritten notes. The

book is so perfectly realized that it’s easy to fall under its spell. The other

morning, I was so engrossed in a letter from Jen that I missed my subway stop.”

T is for Mr. T (born Laurence

Tureaud), who wrote the colon-happy book Mr.

T: The Man With the Gold: An Autobiography. Consider this commentary—how

tongue-in-cheek, it’s difficult to say—by an Amazon.com reviewer known as

2nearsighted: “I have been a huge Mr. T fan ever since the A Team, and I

have continued to follow his career ever since. His book not only is a surprise

in terms of its literary merit, but it's an inspiration. Mr. T came from

nothing, to turn himself into one of the finest American actors, and a beloved

personality. My only lament is that the book is not more widely read, because,

as an autobiography, it ranks with THEY CALL ME ASSASSIN by Jack Tatum, ME by

Katherine Hepburn, and Kareem Abdul Jabbar's GIANT STEPS. In fact, it's better.

Mr. T has a better sense of rhythm to his language; he's more psychologically

insightful; and he has a voice as strong as any in modern fiction—like a cross

between Bellow's Augie March and Joe Frazier. I have read the book several

times, and I recommend it to anyone who likes a true story, well told.”

U is for U2 by U2, the definitive, official

history (published in 2009) of one of the most famous bands in the history of

rock and roll, compiled from interviews given by the four band members. The

band’s origins were in Dublin in 1976. A 14-year-old drummer named Larry

Mullen, Jr. posted a note on his high school bulletin board seeking musicians

for a new band. The quintet that eventually formed called itself “Feedback.” It

included Mullen, bass player Adam Clayton, guitarist Dave Evans (later

nicknamed “The Edge”), and vocalist Paul Hewson (later nicknamed “Bono Vox” and

eventually simply “Bono”). The fifth band member? That was Dave’s brother,

Dick, also a guitarist. But early on, he left Feedback to join another Dublin

band. Ever heard of the Virgin Prunes?

V is for V: The Original Miniseries, a

two-part sci-fi event which aired in 1983. Written and directed by Kenneth

Johnson. It launched a franchise about “The Visitors”—about deceptively

friendly aliens trying to gain control of Earth. But everything is derivative.

The film versions of the story have been said to resemble everything from a

stage play (“The Private Life of the Master Race” by Bertolt Brecht), a short

story (“To Serve Man” by Damon Knight, and a novel by Arthur C. Clark called Childhood’s End.

W is for W is for Wasted, the latest

installment of mystery master Sue Grafton’s alphabet series. Here’s Grafton’s

version of the first 22 letters of the alphabet: Alibi, Burglar, Corpse, Deadbeat,

Evidence, Fugitive, Gumshoe, Homicide, Innocent, Judgment, Killer, Lawless,

Malice, Noose, Outlaw, Peril, Quarry, Ricochet, Silence, Trespass, Undertow,

Vengeance.

X is for The Joy of X: A Guided Tour of Math from One to Infinity. Author Steven Strogatz,

expanding on his popular series for The

New York Times, has been described as “the math teacher you wish you had.”

He explains some of math’s oft-imposing ideas clearly and wittily in areas from

law and medicine and business to philosophy, pop culture and art. Booklist described it as “a high-spirited romp through complex

numbers, standard deviations, infinite sums, differential equations, and other

mathematical playgrounds.” Among the subjects

he expounds upon: how Google searches the internet, how to determine how many

people you should date before setting down, and how often you should

flip your mattress.

Y is for The End of Mr. Y, written by

Scarlett Thomas and published in 2006. It is a book about a book of the same name that no one alive has read—until Ariel Manto does

so. This is how the publisher described it: “Seeking answers, Ariel follows in Mr. Y’s

footsteps: She swallows a tincture, stares into a black dot, and is transported

into the Troposphere—a wonderland where she can travel through time and space

using the thoughts of others. There she begins to understand all the mysteries

surrounding the book, herself, and the universe. Or is it all just a

hallucination?”

Z is for Z is for Zzz… Part of the

“Mysterious You” children’s picture book series, its subtitle is: “The Most

Interesting Book You’ll Ever Read About Sleep.” The author, Trudee Romanek,

discusses everything from yawning to nightmares to sleepwalking to hibernation.

And these three factoids: 1. Mozart was inspired by music he heard in his

dreams, 2. Gorillas who have learned sign language have been known to sign in

their sleep, and 3. If a person lives to be 70, they will have spent 23 years

of their life sleeping.

No comments:

Post a Comment